| |

Letter to Mrs. Eric Hammond

January 3lst., 1898

To Mrs. Eric Hammond

C/o. Miss Babonan 49 Park Street, Calcutta January 3lst., 1898

My dear dear Mrs. Hammond,

Your beautiful letter is far beyond my power to write, so you must be content with a very humble little note bespeaking my sincere love—and constant thought. I cannot find the exact word you see, but before you get this, the whole W. L. S. will have been in hot pursuit of that same word. So you will be able to pardon my failure ! Be sure to make Mr. Apperson send me the paper to read after ! I shall never forgive him, if he tries to do me out of it finally.

Nim* and Honoria will tell you all about my landing. So I will not repeat it, but tell you instead that since I wrote their letters Miss Muller has telegraphed and written, to say she is eoming. So she will probably be here on Thursday evening— and right glad shall I be to see her. The Swami thought it was temper—but her letter makes me think it was rather a desire to leave me perfectly free, and to do what she thought would meet my deepest wishes.

The last 4 weeks of the voyage were füll of joy—the middle 3 emphatically and increasingly so. Now I feel a little bit of England still there, as long as the Mombassa is in port. Indeed they are going to invite me down to dinner before they leave Calcutta. I want you two people to make Mr. Beathy one of your special friends—I have always felt that he was "a little out of it" with you !—and I do want you to see the fine side of him. Read Mazzini and take him as a commentary. In that way you will see how good he really is—and how tender and sympathetic to all the weak and oppressed, and his burning passion for Humanity.

One of the Master's** first pieces of news was that he had had a beautiful letter from you two. He was delighted to hear that you had promised to see that his fortnightly letter was still kept up. Mr. Goodwin told me too that the Swami's delight at Mr. Hammond's last poem was tremendous. He—the Swami—does hope he will treat more of the Sayings in the same way.

The gentleman who was sent to teach me Bengali yesterday began by laying down two little books—"containing our Lord's Sayings in Bengali—which you shall translate as soon as you are able." I think it says world for the unsectarian character of the Swami that my reply was—"Our Lord ?—But which ?— Krishna ?" Fortunately he misunderstood my difficulty and said "Yes, Our Lord, Sri Ramakrishna"—and then I knew.

Indeed you are quite right to think I should be horrifled at the idea of having to "learn to love" anyone ! However, I hope by this time you have been to school in that subject to him.

It is so funny to get to a country in the time of roses and green peas, and to value a rose just as one would do at home. The weather is perfect—not a bit too hot—as one sits writing in a darkened room. Outside, the sun is indeed too bright.

The postman delivers his letters at my bedroom door, and my servant (I have a man of my own, my Dear !) leaves my visitors standing on the doorstep, till I go to them.

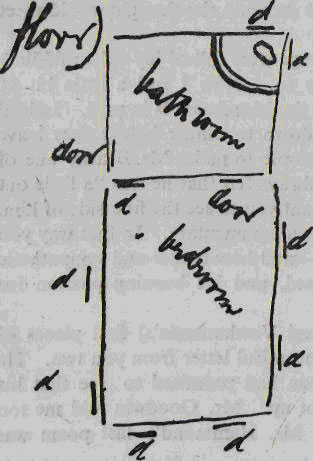

My bedroom has 8 doors though it is quite a small room, and my bathroom, still smaller, has 4,—2 of which open into the bath itself. [(the bath =a Kerb stone of con-crete on a concrete floor) —here in the wall, there is a tap, and on the floor Stands a zinc footbath— beside which you take your stand on a piece of wood and pour water all over yourself with a tin can or sponge.]

So you may imagine that one feels as if one were bathing on the highway of the nations where 4 roads meet. I wish I had a camera to send home photographs of everything. A row of native shops is the funniest thing you can imagine. But I feel very much at home at present, and will try to put all my small surprise into my geography letter.

Your have all been so good to us all. I don't know how we can ever thank you—I knew you would take care of them and look after them, but you have done it so abundantly. Honoria said XII Night promised success. I wish I could hear The Exact Word and Father Brett.

Mr. Goodwin talked of the latter, but Madras also will go into the geog.' This is such a poor expression of love Dear— but I am sure you will forgive. Congratulations to A M on his new poem. Love to Miss Hill and Mr. and Mrs. Forde. Hope Mrs. Jonson's last talk was good. "Tiffin" (lunch) calls—Bye bye. Much much love—

Margaret

* Sister Nivedita's youngest sister May; afterwards Mrs. Ernest Wilson.

** Swami Vivekananda

Letter to Mr. and Mrs. Eric Hammond

Feb 10, 1898

Kindly redirect

Private

49, Park Street, Calcutta

Thursday, Feb. 10th. [1898]

(Quest of the Exact Word)

My dear "Nell" and Mr. Hammond,

The Rev. Mother arrived early on Monday morning last. On Tuesday we saw the Swami. Yesterday we picniced as his guests on a lovely bit of the river bank that Miss Muller is buying for him to build a monastery on. (It was just like a bit of Wimbledon Common—until you looked at the plants in detail. Then you found yourself under not silver birches and nuts and oaks, but under acacias and mangoes in full blossom with here and there a palm in front of you—and magnificent blossoming creepers and cable-like stems instead of bracken and blue bells, underneath).

So you see there has been little time for talks so far.

Today, however, we have been out house-hunting, and for the first time we have come to a clear consideration of plans and activities, outside the merely personal range. I am anxious to write to you and Mrs. Ashton Jonson by this mail and tell you all I know, but I am beginning with you, because to you I shall be absolutely frank, and what I say to her may require more consideration (only in view of her irritability you know—she writes such terrible letters, sometimes as you know wrote one "very stiff" thing to the Master I believe, just before Miss M's 2nd telegram. I know, and you know, that she behaved like an angel afterwards, so she is probably entirely unaware of her literary severity, but I do want to avoid epistles of that nature. At this distance they would cause such pain).

To begin with that bogey of ours—sectarianism. You have always said—in full agreement with Mrs. Jonson—"do let us avoid making a new sect"—and so I have felt—I hate being labelled or labellable. But I have now had time to consider the ease quietly alone and I have come to the conclusion that a sect is a group of people carefully enclosed and guarded from contact with other equal groups. It is the antagonism to others that constitutes a sect—not union. Therefore if members of various sects without abandoning their own existing associations choose to form a group for the special study of a certain subject or the special support of a given creed or movement it is surely no more a new religious sect than the Folk Lore Society, or the Society for the Protection of Hospital Patients or the N S P C C.

At the same time the clear definition of such a group enables it to conserve the co-operative powers of the members instead of dissipating it, gives them area for appeal, and so on. Don't you agree ?

Now that I have got the bearings of the thing like this, the word "sect" seems to me a mere bogey—and our terror of a new one just as great a weakness as any other fear, say of Russians or

scarlet fever.

Now as to the work here. The Swami's great care now is the establishment of a monastic college for the training of young men for the work of education—not only in India but also in the West. This is the point that I think we have always missed. I am sure you agree with me as to the value of the light that Vedanta throws on all religious life : what one does not realise is that this light has been in the conscious possession of one caste here for at least 3000 years—and that instead of giving and spreading it, they have jealously excluded not only the gentiles but even the low castes of their own race ! This is the reform the Swami is preaching—and this is why we in England must form a source of material supplies.

With the educational definition of the aim you are sufficiently familiar. You also know well enough that the spread of the Devotion to Sri Rk. [Ramakrishna] is another way of defining the object which would better appeal to certain minds.

There is another side again.

This Movement is no less than the consolidation of the Empire along spiritual lines.

Mrs. Boole declares that the Theosophical Society is the stalking horse of the Russian Government. It is certain that members of the Theosophical Society have in the recent crisis been inciting the people to sedition and mutiny against us.

On the contrary not only has the New Hindusim found its first firm foothold in the USA and in London, but every one who has joined it actively is passionately loyal to England.

When the Swami is in India at least as regards the Hindu Section of the Community there will be no sedition or the shadow of it. I do think—don't you ?—that the thing is broad enough to appeal to other sections in England outside the Missionary-senders, and when we begin the women's side, all women-leaders ought to be in sympathy.

Next week I shall write again and then only not now—shall I post to Mrs. Jonson. This is merely news and my opinions— what is not personal—if you concur—make known. The work promises infinite joy. Yours with love—always.

Margaret

* Mr. Eric Hammond wrote a poem in The Brahmavadin of

October 1, 1897, Woulds't Thou See God, based on a Saying of Sri Ramakrishna. Nivedita perhaps refers to this poem.

Letter to Swami Akhandananda

49, Park Street, Calcutta

Easter Sunday Morning

[1898]

My Dear Swami Akhandananda,

It was so good of you to write and let me know about the journey. So far I have had no other letters from Darjeeling, only a couple of telegrams.

I was so much relieved to know that the Rev. Mother and Mrs. Bull had borne the journey well. How lovely that the King [Swami Vivekananda] had gone off to see the snow. Of course I am sorry for you, for I am sure you were looking forward to meeting him, but he loves the snow so much !

Why do you say, you take undue advantage of my kindness ? I have never done anything but accept things from you, and cannot think what you mean. I mean to accept more things, too— for I am sure that you will do more of the practical work of our Educational Schemes than anyone else, and you shall be very very hard worked Swamiji ! I think I am so stupid about Bengali, I ought to be talking it by now !

Now I am going to tell you what I have been doing. I took your advice and went straight to Sarada on Thursday morning. It was so lovely. Gopal's mother was there and Swami Brahmananda and Swami Saradananda and some others. It was warm and beautiful and like home.

Then on Good Friday I went to Belur—for the whole day and night. We heard Swami Saradananda at Rishra Hall, and then came down the river and landed at Dakshineswar and the two Swami, Miss MacLeod and I went wandering about the garden. Presently we sat down under the Tree and Swami Saradananda chanted wonderful Sanskrit prayers and the Great Night was all round us and it was beautiful. And our thoughts were full of another Eastern Garden and another Good Friday long ago, when the Disciples' hearts were heavy with the sense of failure ; but it was all peaceful and happy at the foot of the Tree. I do hope, you will enjoy Darjeeling and come back strong and well for fresh quarrels !

Nivedita

P. S. What India wants is good householders, I am sure of it!

N.

|

Letter to Mrs. Eric Hammond

May 22, 1898

The Old New House, Almora,

n. w. p. India

Sunday, May 22nd [1898]

My dearest Nell,

There are so many things I ought to have told you long ago, for I want my letters to make you feel as if you were here in India all the time. And now you see I have reached Almora, the place in the Himalayas where Mr. Sturdy lived and meditated long ago, and the place from where Miss Muller sent me her summons last year. I am so surprised to find how near the world it is. It took us 2 nights and a day in the train to Kathgodam, the railway terminus, across the Plains. Then we posted on by carriages and dandies to Naini Tal, a gay little watering-place by the side of a lake. Then we came here, 32 miles further on, in 2 days' journey. It really is not so near the world perhaps, but as we have done all our travellings in huge caravans, we have never once been away—and I cannot realise the distance and solitude of this little mountain-fortress. I am now with Mrs. Ole Bull and Miss MacLeod, two of the American disciples. I was staying with them at Bellur, the Rev. Mother having taken a house at Darjeeling for the summer, to which I was to go. The Swami was visiting in Darjeeling too and he went over and told her that I had an invitation to join this tour—if she would fall in with the plan—and so the idea now is that I am to go to her either before or after beginning work in the winter for visits. Voyez-vous ? So much for that.

I have often thought that I ought to tell was the Wife of Sri Ramakrishna, Sarada as her name is. To begin with, she is dressed in a white cotton cloth like any other Hindu widow under 50. This cloth goes round the waist and forms a skirt, then it passes round the body and over the head like a nun's veil. When a man speaks to her, he stands behind her, and she pulls this white veil very far forward over her face. Nor does she answer him directly. She speaks to another and older woman in almost a whisper, and this woman repeats her words to the man. In this way it comes about that the Master [Vivekananda] has never seen the face of Sarada ! Added to this, you must try to imagine her always seated on the floor, on a small piece of bamboo matting. All this does not sound very sensible perhaps, yet this woman, when you know her well, is said to be the very soul of practicality and common-sense, as she certainly gives every token of being, to those who know her slightly. Sri Ramakrishna always consulted her before undertaking anything and her advice is always acted upon by his disciples. She is the very soul of sweetness—so gentle and loving and as merry as a girl. You should have heard her laugh the other day when I insisted that the Swami must come up and see us at once, or we would go home. The monk who had brought the message that the Master would delay seeing us was quite alarmed at my moving towards my shoes, and departed post haste to bring him. up, and then you should have heard Sarada's laughter ! It just pealed out. And she is so tender—"my daughter" she calls me. She has always been terribly orthodox, but all this melted away the instant she saw the first two Westerns—Mrs. Bull and Miss MacLeod, and she tasted food with them ! Fruit is always presented to us immediately, and this was naturally offered to her, and she to the surprise of everyone accepted. This gave us all a dignity and made my future work possible in a way nothing else could possibly have done. Isn't it funny ? The best proof I can give you of her real greatness is that she is always attended when in Calcutta by 14 or 15 high caste ladies, who would be rebellious and quarrelsome and give infinite trouble to everyone if she by her wonderful tact and winsomeness did not keep perpetual peace. There is no foundation for this statement in the character of these ladies. It is only my inference about women in general.

Then you should see the chivalrous feeling that the monks have for her. They always call her "Mother" and speak of her as "The Holy Mother"—and she is literally their first thought in every emergency. There are always one or two in attendance on her, and whatever her wish is, it is their command. It is a wonderful relationship to watch. I should love to give her a message from you, if you care to send her one. A monk; read the Magnificat in Bengali to her one day for me, and you. should have seen how she enjoyed it. She really is, under the simplest, most unassuming guise, one of the strongest and greatest of women.

Oh I wish you were here now—how you would love it ! The Master and three monks who accompanied us are staying in the bungalow of Captain and Mrs. Sevier close by, and he comes over every day. He has just been. Tomorrow, however, he goes off alone for a fortnight amongst the mountains. I cannot tell you how real this idea of meditation has grown to me now. One can't talk about it I suppose, but one can see it and feel it here— and the very air of these mountains especially in the starlight is heavy with a mystery of peace that I cannot describe to you.

There is a kind of pine, called deodar (pro. dhe-odhar) very like a larch and very like a cedar, huge, magnificent, and fragrant with the blackberry-odour of English autumns. Up here the dheodhar grows all round us—and adds like everything else to this unutterable depth—so do the snows —the great white range like a Presence that cannot be set aside—towers over there above the lower purple mountains in front and we sit in a rose-bowered verandah and look. The caves would be the right place.

One of the monks has had a warning this morning that the police are watching the Swami, thro' spies—of course we know this—in a general way—but this brings it pretty close, and I cannot help attaching some importance to it, tho' the Swami laughs. The Government must be mad—or at least will prove so if he is interfered with. That would be the torch to carry fire through the country—and I the most loyal Englishwoman that ever breathed in this country (I could not have suspected the depth of my own loyalty till I got here), will be the first to light up. You could not imagine what race-hatred means, living in England Manliness seems a barrier to nothing—3 white women travelling with the Swami and other "natives"—lay themselves and their friends open to horrid insults—mais nous changerous tout cela—

Yours Dear & all my friends as lovingly as ever.

Margaret E. Noble

Letter to Mrs. Eric Hammond

June 5, 1898

C/o. Mrs. Ole Bull

The Old Mess, Almora

Sunday, June 5 th. [1898]

My dearest Mrs. Hammond,

Your letters are always beautiful. I do wish I could worm more out of you !—and your "confessions" are the most beautiful part. I never had a lovelier letter than yours of Friday last, about the London work and the contemplated Retreat and the rest. It seems to be an answer to one of mine written about the end of March—for my new birthday was March 25th and it refers a good deal to that. But I think I have written to you since then and no doubt by this time you have received the letter.

Yesterday was made very very sad for us here by a telegram towards noon announcing the death of Mr. Goodwin. Mrs. Ole Bull and Miss MacLeod knew him better than I, but I was the last who had seen him, he was so good to me that day at Madras, and his goodness was so utterly characterstic of him ! The grief of the Hindus who knew him here was evident and real. One young man who attends us night and day almost, sat here for 3 or 4 hours and scarcely spoke—another, a monk, sat the whole afternoon and told us tender loving stories about him. One man, Badri Shah, the richest man about here, had come to this monk early in the morning saying that he felt sure that his brother Govinda Lall, was dead. When the telegram came, Swami Saddhanda [Sadananda ?] wanted to suppress it, as the King was away, and it was to him, but he could not prevent "some tears rolling down," and this man insisted on knowing the truth. "Well" he said, when he heard, "Govinda Lall or Goodwin, it is almost the same to me." So much the boy was loved. The King is still away and will be home this morning—the blow will be terrible—but one comfort is that he died at Ootacamund, one of the most beautiful spots on earth—and not at that terrible Madras. But he died a martyr to work and climate as surely as if it had been plague instead of typhoid fever that killed him. There seems to have been no lack or defect in his service and devotion. It was full measure, pressed down, and running over —and the first place among the saints of the new Indian era will be held by an Englishman. Incense and flowers and beautiful music are the only offerings bright enough for such a life completed.

And the Western disciples now in India are 6 instead of 7. Now about other things—if you go into retreat on July 20th we also shall keep it here with the Master, they want me to tell you. How the work seems to be going ! Dear Mrs. Jonson, and dear you ! Now that Mr. Sturdy is back, do you get any expression of interest from him ?

I am learning a great deal. To begin with I have begun to acknowledge that English women are probably more spiritual than English men, but Hindu men are far and away beyond them—that there is a certain definite quality which may be called spirituality ; that it is worth having ; that the soul may long for GOD as the heart for human love ; that nothing that I have ever called nobility or unselfishness was anything but the feeblest and most sordid of qualities compared to the fierce white light of real selflessness. It is strange that it has taken so long to make me see these elementary truths clearly—isn't it ? And at present I see no more. I cannot yet throw any of my past experience of human life and human relationships overboard. Yet I can see that the saints fight hard to do so—can they be altogether wrong ? At present it is of course just groping in the dark-asking an opinion here and there, and sifting evidence. Some day I hope to have first hand knowledge and to give it to others with full security of truth. One thing seems very clear—that psychic and spiritual are two utterly different things. I feel— I may be a self-deluded and vain goose—as if the whole realm of the psychic were at one's entire command any time—and utterly undesirable. Mrs. Ole Bull tells me that she has seen terrible results—mind-cure people getting others where they could not extricate them—and so on. On the other hand, it seems possible to do all these things from the higher stand-point safely and happily, if he who has realised GOD finds any reason to will one condition of things rather than another. And I think the London Christian Science in Mrs. Jonson's hands has been entirely subservient to the higher consciousness—don't you ? I know I can have no doubt that it made a bridge for me to the Vedanta as I cannot imagine anything else doing.

Of course you have heard that the Plague has broken out in Calcutta. Probably at this moment you get more up to date accounts than we, for newspapers are rare up here. It is not expected to be bad during the hot season—and the Math is going to have its own hospital if there is an epidemic in the winter. I don't in the least know, in that case whether my work will lie in starting a school as planned or in working on the other lines.

Thank you for all you say about my new position. It came upon me with a sense of amused surprise that there could be any doubt as to the wisdom of my proceeding in any one else's mind. There is none in mine. It is too real for that. To begin with, to take a determined stand for yourself and deliberately shut doors that lead otherwhere gives a certain freedom and light heartedness to life which has been the greatest possible boon to me. And besides this purely personal advantage it has drawn me so near the Hindus. They trust me in such a different way. Before that, we were all "Mother" to them—now, I am "Sister", and funny as that sounds, the latter title indicates a more genuine and individual relationship than the former. There can be no question so far as I can see as to the desirability of the step for the work's sake. Now I want every one I know to get me every Anglo-Indian introduction that they find possible. So please be on the look out. I see great possibilities before anyone here who has a large and influential English acquaintance, in the way of so utterly changing public opinion and illuminating public ignorance that you can scarcely imagine it. It is the dream of my life to make England and India love each other. To do England justice, I think India is in many ways well and faithfully served by her sons, but not in such a manner as to produce the true emotional response. On the other hand of course every nation demands freedom—Italy from Austria, Greece from Turkey, India from England, naturally—and in the course of centuries the Hindu may be equal to the peaceful government of himself and the Moslem. At present the only possible chance of that political peace which is essential to India's social development, lies in the presence of the strong third power, coming from a sufficient distance to be without local prejudice. To my mind it is not unlikely that Russia might rule more beningly from day to day. She would be certain to require of her governors and judges a familiarity with the language of their provinces which to our eternal disgrace we do not demand (ignorant criminals are condemned to death here in the unknown language ! Surely a refinement of cruelty), but on the other hand, Russia's own political imagination is so entirely Asiatic, oscillating between despotism and anarchy, and knowing no third possibility that she cannot surely give the Indian, who are essentially a European people, the range of political development that their history and -capacities demand. But I must be boring you to death with all this speculation, so I'll keep the rest of my paper till I have seen the King [Swamiji]—and have something to tell you of him.

Monday morning. He came late last evening, with his spirits evidently lowered by the news of the death of the old saint who, you remember, called the cora-bite "a messenger from the Beloved." So he was told nothing of Mr. Goodwin's death till this morning when he came here and Miss MacLeod told him. He took it very quietly and has been sitting here chatting and chatting and reading the paper ever since. He listened with great delight to your letter, and looks forward to the poem. Oh Nell, Nell, India is indeed the Holy Land.

We all shared your letter, and the love you sent is warmly reciprocated by these dear loving and noble friends. You never knew anything so "blessed" (to quote Miss MacLeod's favourite word) as this little home amongst the mountains with its utter love and generosity and simplicity. Mrs. Bull is the incarnation of loving—no, love-full sanctity—and Miss MacLeod of fire and courage—and our other guest Mrs. Patterson is a true lover of the Master—which is I know a royal road to your heart. We have been indulging in fun this morning, in the midst of the subdued memory of Mr. Goodwin—and if only the Thompsons had been here to know why Mr. Stead dislike the Swami they would have screamed with laughter. When he is in England, you must insist on his telling you the story of Mrs. Williams, the New York medium, and once started he is sure to tell you all the rest.

I suppose I had better make up my mind at once about the W L S paper for next winter—I think it had better be. "The Mutual Relations of India and England—A Criticism and a Prospect"—or half of that unwieldy title if you please. Do you ever buy "Great Thoughts ?" When you do, will you try to remember to pass it on to me—if you have no better claimant ? I want to be of some little use to the Brahmavadin, and I think that would be a great help. I should be more than grateful for any one's old' 'Weekly Suns'' in the same way. It does not matter how old. Do you know, in my childhood I never could lower my pride to ask even my own mother for food without the most terrible effort—and nowadays I don't mind in the least asking for things like this ? Isn't it funny ?

Thank you very very much for all the news. My poor Nim, I know she must be terribly worried—and it is my fault too. But I feel so so so sure that her burden will not be allowed to grow too heavy and that I shall yet be allowed to do my right and due share in the matter. Meanwhile I am more than grateful to those who are such loving friends to her. It is just your dear kind hearts that I have been thanking you for all this time.

I wish I could see your dear little home in Park Road this minute Nell dear—with the sphynx over the mantlepiece and the skull and crossbones in the corner—what fun we have had there. I do hope you will be there still when I am next in England. The dear walls ring with good fun and good fellowship, and I shall join in it many a time again I quite believe—if you'll have me ! I am so happy—no words can tell you. The King's and all our love. Goodbye.

Nivedita

I suppose if you get it by the middle of Oct. it will do. I have always had the 28th of Oct. or so for my papers !

|

Letter to Mrs. Eric Hammond

August 7, 1898

Between Islamabad and Srinagar

On the Jhelum, Kashmir

Sunday morning, August 7, [1898]

My dearest Nell,

Your last lovely letter, close on the heels of its predecessor, was written on a Sunday morning. Much has happened since then, and it is Sunday morning again. We are on our way

down to Srinagar, and I have a boat to myselfelf—for the Consul's wife has just left us to join her husband. Over there is Swami's boat, and just behind Mrs. Bull and Miss MacLeod's where we have been lunching (our first meal we have about 6—lunch about 12—and our last at 5 or 6). The river is like glass, and a slight breeze meets us in our leisurely progress. It is just like heaven. A few weeks hence all this will be over, and my consolation will be that I gave thanks for every moment of it while it lasted.

Your letter was a delight, and most unexpected, for I have a notion that you hate producing letters. Your other just cams in time to keep us perfectly with you through your week of retreat. Oxford was a lovely choice surely—and how delightful the £5 must have been. May it be the precursor of many such. "Great Thoughts" was such a boon and even Swami read "MAP" through ! How nice it is ! I didn't think a Society paper could be kept so sweet and clean. I shall be grateful to you at any time for a paper like Great Thoughts if you have it by you. It serves better than anything else to show Swarupananda the element that we both think should get into the Prabuddha Bharata.

At Almora he was just my Bengali master, and helper with the Gita. Here, and now, especially with the interest and responsibility of the new paper resting on him over there, I count him one of the best and finest friends I ever had. He is one of 3 Bengali men—besides Swami—whom I am just proud of knowing. I gave your message—"Love and Devotion"—to the Master— he had already brightened up at your photograph (how good it is ! and how lovely and homely to get it ! Oh for a peep into your nest at this moment !) and he said at once : "And mine to them." He thinks the world of you two you know. One day he was building castles in the air, about a sort of farm-colony he plans to have in a scantily populated district of Behar (in some words he thinks it will be centuries hence, nevertheless listen to this) and he ended up by saying—"Oh yes, I'll get Mr. and Mrs. Hammond and heaps of other English workers out here, and they'll do that for me !"

I saved that up for you, and always neglected to tell you, Mrs. Jonson and Mr. Sturdy have both written such warm thanks to you that his heart is just full, and I think that Purity Meeting where he spoke for you has linked him to you in a very special way. I have heard Mrs. Bull tell him two or three times that she thinks it the finest thing he ever did. She has such a lovely-fancy about him. I love to connect and watch people's attitude. To you he is the Master, to me the King, to her the Sistine Child. Isn't that a beautiful idea ? And I think one can't help catching the resemblance too, the minute it

is mentioned.

And now I must tell you something, that will startle you—I have been away up in the Himalayas for a week—18,000 feet high—I went with Swami to see the glaciers—so much anyone may know. The rest you may not tell. It was a pilgrimage really to the Caves of Amarnath, where he was anxious to dedicate me to Siva.

For him it was a wonderfully solemn moment. He was utterly absorbed though he was only there two minutes, and then he fled lest emotion should get the upper hand. He was utterly exhausted too—for we had had a long and dangerous climb on foot—and his heart is week. But I wish you could see his faith and courage and joy ever since. He says Siva gave him Amar (immortality) and now he cannot die till he himself wishes it. I am so so glad to have been there with him. That must be a memory for ever, must n't it ?—and he did dedicate me to Siva too—though it's not the Hindu way to let one share in the dedication—and since he told me so I have grown Hindu in taste with alarming rapidity.

I am so deeply and intensely glad of this revelation that he has had. But oh Nell dear—it is such terrible pain to come face to face with something which is all inwardness to some one you worship, and for yourself to be able to get little further than externals. Swami could have made it live—but he was lost.

Even now I can scarcely look back on those hours without dropping once more into their abyss of anguish and disappointment, but I know that I am wrong—for I see that I am utterly forgiven by the King and that in some strange way I am nearer to him and to GOD for the pilgrimage. But oh for the bitterness of a lost chance—that can never never come again. For I was angry with him and would not listen to him when he was going to talk.

I have a feeling dear Nell that you will have some strong quiet piece of comfort in your brave heart—but if only I had not been a discordant note in it all for him ! If I had made myself part of it, by a little patience and sympathy ! And that can never be undone. The only comfort is that it was my own loss—but such a loss !

You see I told him that if he would not put more reality into the word Master he would have to remember that we were nothing more to each other than an ordinary man and woman, and so I snubbed him and shut myself up in a hard shell.

He was so exquisite about it. Not a bit angry—only caring for little comforts for me. I suppose he thought I was tired • only he couldn't tell me about himself any more ! And the next morning as we came home he said "Margot, I haven't the power to do these things for you—I am not Ramakrishna Paramahamsa." The most perfect because the most unconscious humility you ever saw.

But you know part of it is the inevitable suffering that comes of the different national habits. My Irish nature expresses every-thing, the Hindu never dreams of expression, and Swami is so utterly shy of priestliness, whereas I am always craving for it— and so on. Now that's enough selfishness—only remember I shall tell plenty of people I have been up there—but I shall tell no one what I've told you and you're not to be betrayed into any knowledge of the pilgrimage as anything but a sight.

Your beautiful story of your vision and your most lovely word "reciprocating our highest consciousness" are a perfect treasure. I don't know if you ever got so far as to sit in the Buddha-attitude for meditation. I never took that seriously in England, but here in India one does it quite naturally and simply. And it is quite worthwhile. Swami Swarupananda helped me more than anyone else ever did. Meditation simply means concentration—absolute concentration of the mind on the given point, but there is some subtle magnetic condition which makes it easier—and so external conditions are worthwhile. For instance a skin rug to sit on is quite seriously a help. It isolates one and increases the magnetic power in some way. Swami on the other hand could not bear that—because the physical something would become so overwhelmingly strong.

Swarup[ananda] says "and the minute you succeed in concentrating all your powers for a second, you have done it,— the rest will speak for itself." But long before that—great things come to one—and if it is only the perfect stillness, it is something wonderful, don't you think so ? What Maeterlinck calls the "Great Active Silence".

I have never had this experience of going to sleep, though I have tried once or twice. But I have heard of it.

Then an old Sannyasin lately told me that you should only have two subjects of meditation at first—and of these you should be always in the presence of some picture or symbol, so as to saturate your whole mind with the idea. One should be your Guru—and apart from him one concrete subject besides. After the concrete, one is able to meditate on the abstract.

Do you care for these scraps of information ? I value them because personally they have been difficult to come by—but it is possible that you have long known them. There is something else I meant to tell you but I can't think at this moment, oh yes, about breathing. I was quite out of breath one night, and could not anyhow get quieted down, so I just went on with the mental effort, and presently I noticed that quite unconsciously I was "breathing inwardly" as they call it—and was perfectly in control. It is so curious how the instant a gleam comes to one, one under-stands suddenly the necessity of solitude and so many things that were only hearsay before.

And now I must stop. There is no secret from Mr. Hammond in my letter, it is to you both. I wish it were beautiful and unselfish like yours.

Your own loving,

Nivedita

P. S.—I hope you have had a lovely time.

|

Letter to Mrs. Eric Hammond

September 2, 1898

Private Srinagar,

Kashmir

Replies,

Bellur Math, Ho'wrah, Calcutta,

Sept., 2nd. 1898

My darling Nell,

It has been on my mind for weeks that I ought to write you all the scraps I had picked up about Meditation. I have an idea that when you go to sleep, it is because the body is so ready to pass into quiescence—I am dreadfully jealous ! I should fancy that all you had to do was to keep perception awake, while the body slept, gradually getting the continuity of conscionsness that we want.

I told you about the Concentration that I was told to try for. I found out such a funny thing the other day. I had been trying to see with my eyes. They were shut, but you know what I mean—and really in meditation one does not see with one's eyes, but perceives directly (as it seems) with that part of the brain that lies between them and behind the forehead.

I wonder if you know all this—it comes to me by such snatches that I fancy you want it as badly as I do.

We are going off early tomorrow morning 50 miles up the river, then a Camp in a forest, with the King, for Meditation. In a fortnight's time we shall leave Kashmir, go to Peshawar, Lahore, Delhi and Agra. Then I say good-bye to the others, who are going to hear the King lectures for the Rajah of Baroda, and on to Calcutta to open my school. So this lovely dream will soon be over.

We are camping here on a piece of ground that the Maharajah wants to give Swami for a Sanskrit school. Well, the Missionaries have been stirring up such attacks on the King that it is very very doubtful that the Resident will consent to the disposal of the land —and it is just possible if this happens that I may go for a private interview with the Resident—without Swami's knowledge. I have at least as much right to speak for the Master to the representative of our Government as any missionary against him. As a worker I think it would be good for the movement to be opposed officially, but as an Englishwoman how could one bear England to do the mean thing ?

If the others succeed however I think "Truth" would publish the facts—don't you ?

Swami has one warm friend, a fine little man, Lieutenant Governor of the State. He came last night when I happened to be alone, and he was delighted with my plan, and has promised to think it over carefully. I burn for the honour of England which suffers a moral betrayal on all sides.

This afternoon I have sent my WLS paper off to Nim. If Mr. Hammond thinks it good enough to read anywhere I shall be so grateful for I want it aired in all directions. When I met Mrs. Besant in Almorah, she told me that she had no hope of influencing the English now in India. All her hope lay in enlightening public opinion in England itself—so as to modify the attitude of people coming out. Swami says he held my opinion even two years ago, as to the hopefulness of the matter, but now he despairs. That is after the insults of 2 years you see — but I hope I shall not lose hope about his nation as quickly as he about mine.

He has been away again on one of his lonely journeys. He always comes back from them so gentle and kind and yet witty, and so glad to be with us all again ! It is most delightful. You see this summer has meant 3 months of perfect peace and friendship, and he will always remember it, so I hope.

They are to start for America via China and Japan in a few months. There is a faint chance of the other way — with Egypt Jerusalem Athens and London—but only faint. However, if it happened Miss MacLeod carries your Mr. Apperson's [...] and I think the Thomson's [...] addresses. She declares she must see you all, and will come to you or be at home to you in London to Mrs. Bull as it happens. I think she is really dying to run round and see you all, but I fear lack of time, and for Mrs. Bull it would be nice if you all called.

Anyway, it is Y-Y's [Yum Yum's, i.e., Miss MacLeod's] determination to see you all some day if not now, and Mrs. Bull's too. Mrs. Bull plays plays Grieg exquisitely, and talks about him divinely.

Now about meditation again. I am sure that there is something about breathing—but I think Swami might perhaps have broken up the subject a little more—a few deep breaths for instance, or breathing only through the left nostril perhaps—would do a great deal to quiet the nerves before meditating—only before this kind of thing you are warned that you should be in a safe place in case you fall.

Two nights ago it was the full moon. Already autumn is in the air, and the mountain, mist and clouds shining in the moon are marvellously lovely, all white and glistening. I have never seen that peculiar shining whiteness of great masses against blue mountains before.

Next Wednesday will be your at home again. I wish I could come in and drink your tea, without breaking the charm of this wonderful present and future. Perhaps I shall—who knows ?

When I reach Calcutta I am to stay with Sarada—till I find a house. The latter must be modest—for I have just 800 rupees to carry the school through the first year (£ 53.6.8—my dower we say). I want to take the children at 1 rupee a month—but at that rate I should want 100—I see to renew the income—and that would not support the larger home which 100 pupils would require. So at the end of the first six months I shall probably be in a position to write a report for publication by Mr. Sturdy to be circulated in England and India and through that I shall hope to put the thing on the basis of subscription.

Some of the money that has been going to missionaries may just come to us, don't you think so ?

And now I have a host of other letters to write. Was it you who sent me Great Thoughts twice ? Thank you so much.

Give my love to everyone—and yours to my precious Sister.

Ever your loving friend,

Nivedita

How could I be so mean ? . I told you nothing of the lovely visit the King paid us yesterday, and heard my paper—and talked about the history of India—and brought us scraps of things he had been writing, for our inspection and approval. Like a child.

Here is a translation of a Bengali poem by Ram Prasad.—

What use is there in going to Benares ?

My Mother's lotus feet

Are millions and millions

Of holy places.

[Pages missing]

|

Letter to Mr. Ebenzer Cooke

September 18, 1898

Kashmir

My dear Mr. Cooke,

I only hope you have been able to go off with the boy for long rambles in the wood and by the river. I should like to think that your holidays had not passed without your once catching sight of the bright eyes of a field mouse, or hearing the rattle of a snake ! —and I do hope you took some pictures ! I want them so much to have seen Persephone and Spring and those Greek-looking pencil drawings. I was so delighted about Mr. A. And the more pleased because your long silence made the blow more effective. Fighting about trifles is worth so little. The great far-reaching forces of one's activity bear their slow-coming fruit in the distant future, regardless of one's personal attitude to A. or B.

In about 7 or 8 days I go off "All by my lone" to Calcutta-examining on the way Lahore, Delhi, Agra and Benares. Once in Calcutta I hope soon to be at work—and won't I work !

When you are teaching hard you can think of me doing the same. I'm not an atom disappointed in India so far. You will be amused to hear what my school fees are to be—4d. a month per child ! ! ! ! That, it seems, is the missionary fee. India is a grand harvest of illustrations for the Socialist. It is far easier to get charity here than one's honest due, and consequently all kinds of labour, but especially mental and professional work, are underpaid.

As for the attitude of the English to the native—oh, you would blush as I do if you could see it all.

My impression is that the Oriental mind does not conceive of bribery and letter-opening and things of that sort as quite such abysmal crimes as they seem to me. It is difficult to me to believe that our highest officials would take bribes quite so easily as one hears them accused of doing. On the other hand, I have so often seen that a man proved guilty of sins one could not imagine his committing, when first stated, that I ask myself—"What do I after all know of these things ?"

|

Letter to [ ? ]

Oct. 13th., 1898, Thursday

But I really sat down to tell you more about Swami, and I don't know how to begin. He left us yesterday, and we may see him again at Lahore, or not till we reach Calcutta.

A fortnight ago he went away alone, and it is about 8 days since he came back, like one transfigured and inspired.

I cannot tell you about it. It is too great for words. My pen would have to learn to whisper.

He simply talks, like a child, of "the Mother"—but his soul and his voice are those of a God. The mingled solemnity and exhilaration of his presence have made me retire to the farthest corner, and just worship in silence all the time. "We have seen birth of stars, we have learnt one of the meanings."

It has just been the nearness of one who had seen GOD, and whose eyes even now are full of the vision.

To him at this moment "doing good" seems horrible. "Only the Mother" does anything. "Patriotism is a mistake. Everything is a mistake"—he said when he came home. "It is all

Mother----All men are good. Only we cannot reach all

----I am never going to teach any more. Who am I, that

I shd. teach anyone ?"

Silence and austerity and withdrawal are the keynotes of life to him just now and the withdrawal is too holy for us to touch. It is as if every moment not spent with "the Mother" consciously were so much lost.

---- ---- ----

As I look back on this wonderful summer I wonder how I have come to heights so rare. We have been living and breathing in the sunshine of the great religious ideals all these months, and GOD has been more real to us than common men. And in those last hours yesterday morning, we held our breath and did not dare to stir, while he sang to the Mother and talked to us.

He is all love now. There is not an impatient word, even for the wrongdoer or the oppressor, it is all peace and self-sacrifice and rapture. "Swamiji is dead and gone" were the last words I heard him say.

----

Nivedita

Letter to [ ? ]

October 13, 1898

[Pages missing]

Ever since the day he wrote "Kali the Mother", he has been growing more and more absorbed, and at last he went off quietly without any one knowing, from the place where he was living to a Sacred Spring called Kir Bhowanie. There he stayed eight days, which seem almost too holy to write about. He must have had awful experiences spiritually and physically, for he came back one afternoon, with his face all radiant—talking of the Mother and saying he was going to Calcutta at once.

Since then we have hardly seen him. He has been alone and living like a child "on the lap of the Mother"—it was his own expression. How am I to tell you of things that [ ••• ] But I want you to know it as if you had been here. I know you won't treat it as news or as anything but sacred to yourself.

My own feeling (mind that is all) is that the ascetic impulse has come upon him overwhelmingly and that he may never visit the West or even teach again. Nothing would surprise one less than his taking the vow of silence and withdrawing forever. But perhaps the truth is, that in his case this would not be strength, but self indulgence and I can imagine that he will rise even above this mood and become a great spring of healing and knowledge to the world. Only all the carelessness and combativeness and pleasure-seeking have gone out of life and he speaks and replies to a question with the greatness and gentleness of a soul as large as the universe, all bruised and anguished, yet all Love. To say anything to him seems sacrilege and curiously enough the only language that does not seen unworthy of his Presence is a joke or a witty story—at which we all laugh. For the rest—one's very breath is hushed at the holiness of every moment.

Can I tell you more ? The last words I heard him say were "Swamiji is dead and gone" and again, "there is bliss in torture." He has no harsh word for anyone. In such vastness of mood Christ was crucified.

Again he said, he had had to go through every word of his poem of "Kali the Mother" in his experience,—and yesterday he made me repeat bits of it to him.

He talked, and because he talked of the Mother, the words seemed large enough. Before he had gone away he left one filled with the Presence of the Mother. Yesterday, he made me catch my breath and call him "God."

We are one part of a rhythm, you and I, that is larger than we know of—God make us worthy of our place. "Mother is flying kites", he sang, "in the market place of the world, in a hundred thousand. She cuts the strings of one or two."

"We are children playing in the dust, blinded by the glitter of dust in our eyes."

He turned to us Sunday and said,

"These images of the Gods are more than can be explained by solar myths and nature myths. They are visions seen by true Bhakti. They are real."

Kashmir. Oct. 13, 1898

|

Letter to Miss J. MacLeod

Dec 7, 1898

16, Bose Para Lane,

Bagh Bazar, Calcutta

Dec. 7, [1898]

My Dearest Yum,

Do you expect me on Saturday or not ? I am really writing to say that Miss M [Muller] came yesterday—Wednesday—and stayed 4 hours—on purpose to see Swami as she afterwards acknowledged. It was very interesting and kind, but when she had gone, one felt heartsick.

She has thrown everything overboard, Shri R. K.—Swami— Meditation—University of Religions—everything. She does not hesitate to say that Hinduism is Eroticism to the core, and that its truths have been "kept from her." By whom ? "Oh names are useless"—she answers. All, meditation included, is "dirty."

She is now a Bible Christian of a virulent type, and tending towards millennialism.

My only relief came when I found that "Betsy and me are the one true church, and Betsy's a little peculiar." She does not agree with "these stupid missionaries." Thank heaven—and hope that springs eternal dances over my approaching conversion—and future career in keeping a Xtn school here—(my peculiar notions of honour would prevent my using Swami's basis of money and influence here in such a way—but this never occurred to her) and touring through India preaching Xtnty.

I spoke of Swami—"Oh you won't love him long !" she

answered gaily—Divine Master ! ---- ---- ----

So I was sympathetic and talked Xtnty and the Bible— occasionally reminding her that at present I was not serious being devoted to Swami. If you want to know more come and hear. Love to our Grannie and yourself Dear,

Margot

|

Letter to Miss. MacLeod

June 7, 1899:

He [the Swami] talks of taking me to America and setting me to lecture under a bureau, and so earn money we shall need. How glad I should be! Of course, I cannot tell whether his idea that I should be popular would be fulfilled. I should just love to do it, however, I might go to the same towns where Ramabai had been - and lecture there. Wouldn't that be fun? If, in addition, I could form a huge society, each member of which in England , America , and India should contribute a minimum of one penny or two cents or one anna per annum - that would be grand. The work would never want money. Such are the plans that occur to me. You will sit in judgement of them. I believe in tiny subscriptions to work done for the people, "by the people, as a joy to the maker and the user".

Excerpt from letter to Miss. MacLeod

July 05, 1899

Nivedita wrote of the farewell reception given to the Swami at the last house he visited in Colombo on his way back to the Golconda :

"Last of all, driving down to the quay, we had to enter a house where we were met outside by drums, fifes, and tom-toms. Inside a dense crowd, and fruit on a table. Oh what a crowd! And how they looked at Swami! ... He pointed to his European clothes, but it made no difference. He was their Avatar, just the same. Then he took a small fruit, and sipped milk.... And then as he turned to go, you should have heard the shout, "Praise to Shiva, the Lord of Parvati! Hail!" it was deafening, and you should have seen the crowd in the street when we got out! And the crowd on the landing stage! Them came our first host and hostess back to me us off with endless presents, the hostess, Lady Coomaraswamy, was an English woman, her husband. A Madrasi Hindu, such a fine man! And there that quiet Europeanized-looking-member of the Government stood, and three times called aloud the praise of Shiva, and then three times "Swami Vivekanandaji Ki Namaskar!" ["Salutation to Swami Vivekananda"]. While the crowd cheered. we steamed away to the Golconda . . .

|

Letter to Miss MacLeod

August 3, 1899

21 High Street, Wimbledon. August 3rd, Thursday afternoon My sweet Yum,

We arrived on Monday morning, met at unearthly hours by mother, Nim, Miss Paston, and the two American ladies Mrs. Funke and Miss Greenstidel.

The King spent Monday in Town with these friends, meaning to take rooms near these friends. But he turned up here early on Tuesday morning thinking Wimbledon best after all, and already the family have had 2 huge talks. Nim seems to please him, and he likes Rich.

Nim found him lovely rooms, near the station, but in green and quietness. They cost 35/- a week—which I hope Mr. Sturdy will not think too much and I buy food for him and mean to send in the account to Mr. Sturdy. While here I trust men will come to him. But meantime he says he is in perfect peace. He heard from Mr. S. on arrival but refuses to authorise me to do anything yet about American passages. And you know I obey blindly. He says the situation will develop itself—"Mother knows." Thank goodness. The Mother does know ! Oh what a relief to think that one's dealing is all with Her and him, really! That neither jealousy nor criticism of others matters a straw! "My feet are on the Rock that is higher than I!"

I think I should cry if I could see you - - - - Why? I don't know. Mere folly!

Your letter posted last to Calcutta reached me this morning. Oh Yum! It seems too dreadful to think of Mr. S. talking of Swami's learning to be expedient. "Swamiji's work a great and lasting success" indeed ! He can afford to do without any touch of their success—thank heaven—

As to the criticism of expenditure. It makes me ill. I knew there was a flaw in that crystal. But how much easier to face a situation that one understands. For Swamiji to be himself is the same as the shining of the sun. It is enough in itself, without consequences.

One thing I can see. He is letting things drift just now—but I can see that he will NOT allow E.T.S. to manage him this time! He said ''you know I am always best when I strike for myself." He quoted again that Sanscrit definition of a friend'—"In pleasure as in pain—in goodness as in wrongdoing—at court or by the grave—in heaven and in hell." He said you and S. Sara were that but even he couldn't have more than a dozen such! But when I begged him (as I own I did) to go at once to America —cutting off from me, and only to come back to his English disciples when he had you behind him, he said "at the beginning it would have been the time to think," meaning, when he first took them for disciples he might have been permitted to see their faults, not now. And of you he said, "You know I have told you—she is my good star—but she is broken up. She must rest. She will not rest long—neither she nor I can do that, and she strains every nerve to find me the money I want. She must not do that. I will not be a burden."

About M. Nobel. No doubt he has written you. M. Nobel was all that was thoughtful and polite, but it was not his best moment for receiving Swamiji and the King did not go.

Oh Yum, the other night with Mrs. F. and Miss G. he told me such wonderful things! He used to go into Samadhi, not knowing that it was, when he was a little boy of 8! And I asked him about dying, he had told me that he knew what it was like —and he said—

"Twelve or fifteen years ago, in a little hut on the side of a mountain (in Hresikes) was Turiananda and Saradananda, and I. I was very ill with fever and I was sinking and sinking gradually and then there came a moment when I was cold up to my shoulders, and then I died away—and away------and away

----- and then I revived gradually. I had something to do

----When I came back Turiananda was reading Chandi (about the Mother, a Puran) and Saradananda was weeping."

And I was talking to Turiananda about it, and he said it was a miraculous cure.

The night was dark and stormy, and at that awful moment when it seemed that He had gone, came a sannyasin outside the door, saying in a loud voice—"Fear not Brother" and he entered in and looked at Swami and said he knew a certain medicine that would cure him and where it could be got. But it was far to go, and even as Turiananda was hesitating about leaving Him. (for S. was sleeping, to be ready for his turn at watching) came another monk—who volunteered to go and bring it. He went, and came and Turiananda gave the drug, and 5 minutes later death gave place to life—and He was there once more-----

About the Samadhi he spoke in explaining the Hindoo wish to remain conscious and call on GOD up to the last minute. "That picture that you end one life with begins the next" he said —and told this and his love for sannyasins as a proof.

Dearest, do keep my letters, and let me reread them, may be I can continue the diary from them. The only thing I would choose to do if I could earn some money to start with, would be to take a room with a wooden floor, a writing table and chair and sit and write, and go out to lecture, in New York. I am so glad S. Sara approves of my idea about Ramabai—and how good of her to talk of paying the fare.

I don't think I meant to attack anyone in the way you seem to have understood, but I think I'd like to be free anyway. This sounds funny, but you understand! One cannot tell how a public moment turns. And Swami has said so often that I am to search deep into my own inspiration and then trust to nothing else. That seems to me one of the advantages of the plan he has suggested—of magic lantern slides and so on. One, goes-out into the wilderness and seeks out a new audience—only where Ramabai has been is an interest already created! Could you put this to S. Sara for me as it is meant? I had a very -exhausting day in London yesterday with Turiananda and Mr. Chakrabarty and I can't put things rightly today.

I’m just dying to come and read the Diary with you! I wonder if it can be true that I shall see you soon. I am sure it is—but at this moment it is unimaginable. You are wonderful Yum, or you could not remain happy in Western life. It is a prison.

Nim is so quiet about her future. And how lovely she looks and is! It was an awful moment when I saw her first. I had neither thought nor felt, up to that moment, and all at once—and she, too, standing on the quay, cried. She said she felt as if a grave had been opened.

What you say of pedagogy chimes in with my feeling. It stifles me now. It was good training to understanding the Hindu idea—but beyond a certain point, it is the most miserable narrowness. All this of late. If Mrs. Coulston really wants to help do make her study ambulance work!

I own that I am sore about people having left London without making special arrangements to wait for Swami. That would have been nothing to do for him. He on the contrary says he has never been in such perfect peace and laissez faire as ever since I told him.

The frocks you have sent are divine. What a Mother you are! But will you explain to your family that I am to appear in your costumes? You know I do not feel better for truth being Concealed, but quite the reverse. How I WISH you were here! And how I hope to see you soon? Is there a chance of any work for me to start life on? I fear the Ashton Jonsons can't come. Your sister is blessed to like Mr. McNeill.

Yours own loving Child

Margot

Mrs. Gibson has gone, but Nim will take any chance that occurs of entertaining Swami at the Sesame for S. Sara. He is so pleased. And Cookie will help.

One thing that He said this morning was—he could not be a burden on Mrs. Bull. What would her daughter think?

Letter to Swami Akhandananda

Aug 10, 1899

21A High Street Wimbledon, London S. Thursday Aug, 10th 1899

My dear Akhandananda,

All through the voyage, I have been intending to write to you—and tell you how often and how warmly Swamiji has spoken of you for the way in which you have struggled to do and carry out the ideas that we have all received. He seems to place great confidence in you—and to approve of all your efforts in a very special way.

I am sure it would have done you good if you could have heard even one or two of the many things he has said.

I hope the little work on Physics is nearly through the press, not so much because I want Dr. Bose to have the original, as because I should like to see the Bengali work when I come back. But I do not think that your friend can possibly understand what is meant by some of the materials. If he would write out a list of questions or allusions, on which he wants help, I would try to get them elucidated for him.

In a museum the other day I found a most beautiful curved ivory Durga. Swamiji said that it was easy to get such things in Mursidabad. Are these very expensive? For I hope to do some interpretation of our Hindu Symbols in the West, and if a brass or wooden Durga were not impossibly expensive, I should be very glad to have it. Ivory is of course out of the question. I am afraid you must address your reply to C/o F.H. Leggett, Ridgely Manor, Stone Ridge, New York, U.S.A. It was quite small.

Swamiji was in splendid form when he landed—apparently —but he has begun to suffer again, off and on, and he means to go on quickly to America, where they will take care of him.

I am to wait here till a family wedding is over, and after that I am to follow him, and start work in America, too. You must ask Sri Ramakrishna to let me be of some real use to Him, as well as my girls. I am sure He will let me find the money I want for them—but Oh! How I want to do something for my Guru himself ! England seems very petty to me. The Society is so unsympathetic to our real life that I find myself longing for India all my time! So the Mother must grant me some of my prayers to make up for sending me away—Must She not ?

This is the holiday season here, and few people are to be seen. But still, some who "Loves the Lord" gather round our King and Worship Him there.

Ever dear Swami—

Your loving First-of-many Sisters,

Nivedita

Letter to Miss. MacLeod

Aug 12, 1899*

21 High Street, Wimbledon

My sweet Yum,

The king is this morning far from well. He went to see Miss Soutter yesterday, and came home late—but he panted so hard that it took half hour from the station to his rooms— a walk of 4 to 5 minutes. I took a letter down to him this morning from Mr. Sturdy, which also enclosed others from you and S. Sara. I hope it will hasten his departure to America—for I dread this heavy climate for him—though of course heaven would lie, for me, in coming with him.

He asked me yesterday—when can you be ready for America ?

—As soon as you like Swami.

—What? Not even stay and see the sister married ?

—Oh yes I think I ought to do that—Don't you ?

—Yes. Another month—isn't it ?

—But, Swami, let me book the berths ! .

—I think we ought to wait to hear again from Y and Mrs. Bull that we are really wanted.

So I told him of course that we had heard—but now comes the news that E.T.S. will be here tomorrow—and that you know will enable us to make definite plans.

Meanwhile, Dearest, I must write to you. For I am just heart-sick at a touch of suffering in him and I have been haunted all Church-time. I won't say any more about it—Yum Dear—but just to talk to you is enough.

Mrs. Funke and Miss Greenstidel are with him much—and that is a comfort, for he cannot come up the Hill. I feel most awfully cut off from him in some ways—and so astonished that my own family and everyone in Wimbledon are not straining every nerve to be with him all the time ! Altogether life here gives one a lost feeling. Mrs. F. and Miss G, love him as we do, I can see—but they do not trust me much yet.

They think they must conceal Swami's visits to them and so on. And I want to take poor Miss Greenstidel into my heart because Swami loves her so—but I fancy my manner repels-/her. And then, why tell him of the sins of Lansberg and Abhayananda? I should like to keep these things from him if I could, and leave them in his love, without letting them, poor things, stab him. As to his Baby who has gone

back to acting—Isn't his love for her the one perfect link?

There Yum—that is where 1 have got to—the one yearning; feeling in my love how is to take in every soul that he has ever looked on—and love it and serve it to the end—and you 'who passed that way huge times ago—have brought me there.

Isn't it perfectly ideal, to have him to love, and you to show one how? However Mrs. F speaks very seriously of the attacks on him. I told her how I hoped to do something in that line—and she says then they will say he is a libertine.

Don't you see, Dearest, this is one of the things that shows how little one can lay down a skeleton of lectures before hand?

There must be a positive something. Even from me, if I am to win the confidence that is essential? Anyway I am just dying to be with you and S. Sara and Swami and have it all settled.

What about the Diary ? I almost think when I have read it to Nim and Cookie that I'll send it on, as it is.

Cookie is in it all. He had been to hear Earl Barnes on St. Francis.

And as he stood on the steps of the Church after, ETS. came up to him and said in a low voice "Don't you think the world is about ripe for another Christ?"—and then Cookie asked him if he had met Swami. He is going to arrange a little dinner-group at the club, he hopes.

I went to Church—How unutterably and awfully mean and low it seemed. Oh this soul that we have taken knowledge of! Yum Yum Yum. What last year was! We three shall make one devotion to him one of the great things of history—shan't we ? And I see now that is all one asks of people—Do you love him ? If they do, their presence makes rich.

Nim worships S. Sara and calls you her "fairy God-mother." She says she never dreamt of well-dressed saints before. Yum, green and brown frock fits me like a glory—the white is glorious, but I have not tried it yet.

Margot

*This letter appears to have been written on August 5, 1899 not as has been dated August 12, 1899

Letter to Miss. MacLeod

Aug 12, 1899

21A High Street, Wimbeldon, Saturday morning

My dearest Yum,

In a perfect whirl I sit down to tell you before I left. That Swami starts for New York from Glasgow by Allan Line on Thursday the 17th next—and that he wishes me to follow him as quickly as I possibly can,. after Nim's wedding—Sept. 6th. He means to drop Turiananda in New York, and leave him C/o Miss Waldo or someone. He goes on to you. He says he will shut himself tip in a room and live on fruit and milk and get well.

I see many avenues of work in England, but feel also the inestimable benefit of being allowed to recoil from Santer. And Swami says I am to follow or he does not leave it to my judgment. I reached the Sesame yesterday, and received your note and Albert's sweet letter. So I see that your plan is exactly what happens. But don't expect Mr. Sturdy or Mrs. A. J. I am almost sure that it will be hopeless. Mrs. A. J. comes here tomorrow and I do my level best you may be sure. With Mr. S. I have already tried and failed. For my own part I feel as I have always done that he who counts on ETS as a leader fails. Therefore if Mrs. A. J. comes and he does not I shall feel thankful, for both facts.

Now as to passages. It is such a relief to fall back on Mrs. Hull here. I must go by Glasgow and Mr. Sturdy told me to be sure to go 1st class—which they say will cost about £10-10. And how much money must I have in my pocket on landing? I fancy there is a boat Sept. 15th, and Mrs. Funke says I should give at least 2 week's notice.

Don't mind about 1st class. I think the chief consideration is the pleasure of those who meet and see you off. For myself I don't think it in the least consistent. We arranged a tea party yesterday at the Seasame according to S. Sara's wish. We were to have had Earl Barnes, Mr. Keney and some people from one of the London dailies—Swami came and none else !—'except Cookie. Wasn't that too bad ?

Nim's fiance' is here and I must run

Your loving Child

Margot

Letter to Miss MacLeod

21A High Street, Wimbledon Aug. 17.1899

My dear Yum,

My telegram of yesterday morning told that Swamiji was on his way to you. His last words to me were—"Come on as fast as possible." So I can only hope that Mrs. Bull's care of me will take the form of a command to sail on September 7th. M.* marries on the 6th, and if commanded I could come on doubtless at once. Otherwise, it will be a week later by the Allan Line from Glasgow. However, as I have no power to make these arrangements for myself, I leave the matter entirely to you—in either case. Your letters have been endless joy, and so far have been shared with him, but as to answering them—till he went, yesterday morning—I had not had time to breathe. Now, there is enough time, but such a blank! However I do trust that he is having a good time this first evening—for he set sail from Glasgow Dock an hour or two ago.

I received Albert's sweet letter last Thursday and will answer that and all others as soon as I have strength and breath to read them over.

I am delighted with N's fiancé, and he in turn kneels at the feet of the Master, as do mother, Nim and Rich. It is all wonderful.

But personally I yearn to be able to look with Miss Muller's eyes and think that he could fail, and then be faithful. If he were a common man, or nearer it, unloved, obscure or hated, one's love might be worth something; as it is it is a little thing to worship him for whom the very stars must fight. For that room and chair where he is throned seems to me the very centre of the universe—and so you see Yum dear, it is as if we loved one who was rich. Imagine GOD against him—and conceive the joy of standing by him then!

My love to my new sister,** and tell her that if I were not an angel I should be jealous of her!

Margot

Your frocks are LOVELY especially the white—which I am to wear at the wedding. The box is also lovely—you are the best of mothers!

Friday morning

Just a word—to say that your divine letter is here. Oh that dream about the "real name!" I am longing to get to you, and tell you many many sacred things I could not tell in letters— a word here—a hint there—and one—most precious of all—about this real name.

It is useless to try to confine one's place to him in one word. It may be daughter sister friend in name—because a word its convenient for the world to hear, but if One touch you and me in some after life—it will be but natural—as we waken to the Ineffable Memory—to say "My Beloved, My beloved " till we die.

There is nothing worth doing—save to worship him. There is no place worth having—save that of the dust upon his feet.

You will worship him for me – as I have done for you—all this time- when he reaches you.

M

Mr. Beatty said he had dreamt that people like Mrs. Bull and Miss MacLeod existed, but he had never really believed it till he met you two!

Cookie spoke of Albert as one of the supreme trio—her mother, aunt Jo and herself.

The Appersons come home tomorrow night. Saturday I dine and sleep at the McNeils'. My heart to S. Sara, to whom I shall not write. I do hope there is a letter tomorrow.

My love and thanks to your glorious sister. Do make the Grannie hurry!

Infinite love to yourself Dearest.

*May, Margot's sister. She is also nicknamed Nim.

** Olea Bull

Telegram to Josephine MacLeod

Aug 17, 1899

Swamiji is starting today Allen* Line. Numidian. from Glasgow.

(*actually Allan State Line)

Letter to Miss. MacLeod

Aug 19, 1999

21, High Street, Wimbledon

My sweet Yum Yum,

Your registered letter has just arrived containing 2 post office orders for £10.5.4 each—making a total of £20.10.8. I do not expect my ticket to cost more than 10 guineas, but there is another £2 to Glasgow, which will bring it close upon the £15 you name, and the balance I shall hand over to Mrs. Bull on landing, but it is a great relief to have it—in case any difficulty about certain books Swamiji ordered—for which I hope to get Mr. Sturdy to pay.

Of course what you say is quite true about my waiting a month. I am only grateful and obedient to those beloved ones who have so much experience and who will use it all to give me a chance of doing royal work. I wish I were on my way to you now, but how you will love having the King to yourselves! And it is clearly my duty to see Nim through—up to September 6th is a transition period. The day after I start for America a free woman.

My dearest Yum, when you talk about clothes I feel just a humbug. What renunciation can there possibly be in having one's clothes looked after by Mrs. Leggett and you ? You

know very well that I never did have clothes—and though I love pretty ones I really think I like them better on you ! It is quite absurd of me to make professions and things and come out richer than I ever was in my life. That's about what it amounts to. Money was always more or less of an anxiety and difficulty and now—when I really meant to be poor—it is a matter of indifference ! This is not right ! However, Dearest, you know best about this first month—and I shall obey—and then we can settle all the rest.

As to Mr. Sturdy, by this time you know that he has been— and when Swami comes you will hear what he has to say. I can only say that Mr. Sturdy's marriage never seemed to me a fatal mistake till I saw the moral rot that seems to have set it in his character. As Nim and I say to each other—to be Swami's chief disciple and the one on whom all depends is too great a privilege for anyone to be forced into it. He pleads expense as a reason for not going to America with me—and so, with solid treason I feel sure, do the Ashton Jonsons. They would love to •come—but for this year they simply "cannot." What the King says is true—"When I come back to London Margot, let it be as though I had never been here to do a stroke of work." That is the only way—but we shall do great things here for all that. If I were staying, even now, I could make things open up.

Again Swami is right. Work like this requires persons like you and myself who have no other object or thought in life. The Householder Disciple is always a failure, when he leads. As follower he does very well.

By the time you get this letter you will have Him with you— so you will easily be tired. I think of leaving the Diaries* as they are, and sending them on uncopied and unbound, by registered post, because the sooner they are in your hands the better I now think. I allowed Mr. Sturdy to read them through—and only you can settle who else shall see them. Many and many a bit I'd love the King to see—If I didn't know he was looking. In a general way, I would like him well enough to read them, but when it comes down to detail ---------

I can see quite well however that S. Sara might think with a little re-editing that they should be privately circulated. She would do that best—and you umpire.

Margot

The diaries later became the nucleus for two books 'The Master As I Saw Him' (first published in 1910) and 'Notes of Some Wanderings with the Swami Vivekananda'. Both are available on this site.

Letter to Swami Vivekananda

Aug 23, 1899, Wednesday morning

21A High Street, Wimbledon

My dear King*

In a few days more you will be at New York where I hope and believe that Yum herself will meet you.